| Impact | Shaped global politics • Influenced international relations • Shaped popular conceptions of societal progress |

| Debates | Whether all industrialized nations truly qualify as 'civilizations' or if there are more stringent requirements beyond just technological advancement |

| Purpose | Distinguish industrialized, urban societies from traditional, agrarian ones |

| Concept emerged | Late 18th century |

| Expanded criteria | Political organization • Cultural achievements • Social complexity |

| Initial associations | Technological progress • Economic development |

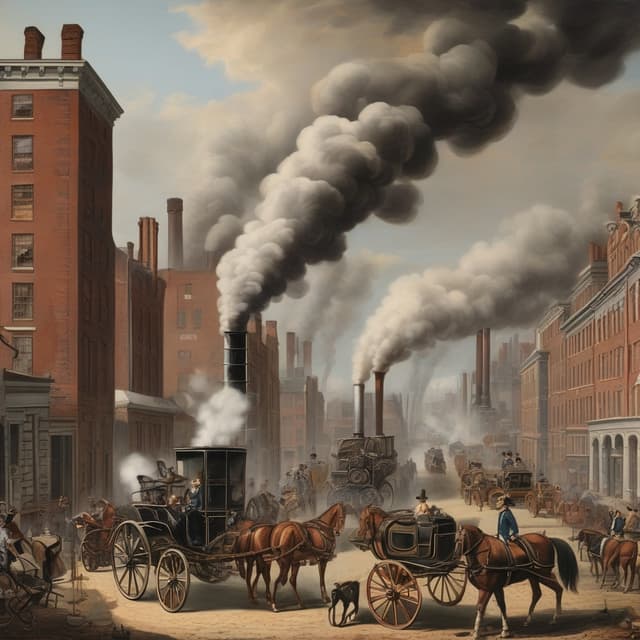

The term "civilization" is a relatively modern concept that emerged during the Industrial Revolution of the 18th and 19th centuries. Unlike in our timeline, where the idea of civilization has ancient origins, in this alternate universe the notion of what constitutes a "civilized" society is closely tied to the rapid technological, economic, and social transformations of the industrial age.

The first recorded usage of the term "civilization" dates back to 1772, in the work of French philosopher and economist Anne Robert Jacques Turgot. Turgot used the word to describe the process of societal development from a state of "barbarism" to one defined by technological progress, growth of cities, and the rise of commercial and political institutions.

This early conceptualization of civilization was heavily influenced by the sweeping changes brought about by the Industrial Revolution, which was just beginning to take hold in Western Europe at the time. Proponents of the new industrial order, such as Adam Smith and other early classical economists, championed the idea of civilization as a state achieved through the expansion of trade, manufacturing, and the accumulation of capital.

Over the subsequent decades, the definition of civilization expanded beyond just technological and economic markers. Philosophers, historians, and social scientists incorporated factors like political organization, cultural achievements, and social complexity into their criteria for what constituted a "civilized" society.

Influential thinkers like Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel and Auguste Comte argued that the development of stable, centralized states with sophisticated legal and bureaucratic systems was a key hallmark of civilization. Others, such as Matthew Arnold, emphasized the role of the arts, education, and "high culture" in separating civilized peoples from the "uncultured" masses.

By the mid-19th century, the concept of civilization had become closely tied to European colonialism and notions of racial and cultural superiority. "Civilizing" indigenous populations through the imposition of Western institutions, values, and technologies became a justification for imperial expansion and exploitation.

Even as the criteria for civilization expanded, debates continued over exactly what thresholds a society must meet to be considered truly "civilized." Some scholars argued that mere technological or economic development was insufficient, and that deeper cultural, political, and social transformations were necessary.

Proponents of this view, such as Oswald Spengler and Samuel P. Huntington, posited the existence of distinct "civilizational" blocs - such as the Sinitic Civilization, Islamic Civilization, or European Civilization - each with their own unique historical trajectories and cultural identities. They challenged the notion of a universal, linear path to civilization.

Other thinkers, particularly Marxist and anti-colonial theorists, rejected the very concept of civilization as a cover for Western chauvinism and the oppression of non-European peoples. They argued that the markers of "civilization" were themselves products of unequal power relationships and the violent imposition of the industrial capitalist order.

These debates over the nature, origins, and validity of civilization continue to shape global politics, international relations, and popular conceptions of societal progress and development to this day.